Google offers free tools for testing your website’s speed. One of them is PageSpeed Insights. If you’re here, you’ve probably already tried it, and are disappointed with your score. The search engine is pretty harsh when it comes to evaluating web page performance, and we’re going to see why it considers your loading times to be not good enough, and also, how to read and put this score into perspective.

Understanding how the PageSpeed Insights score is calculated

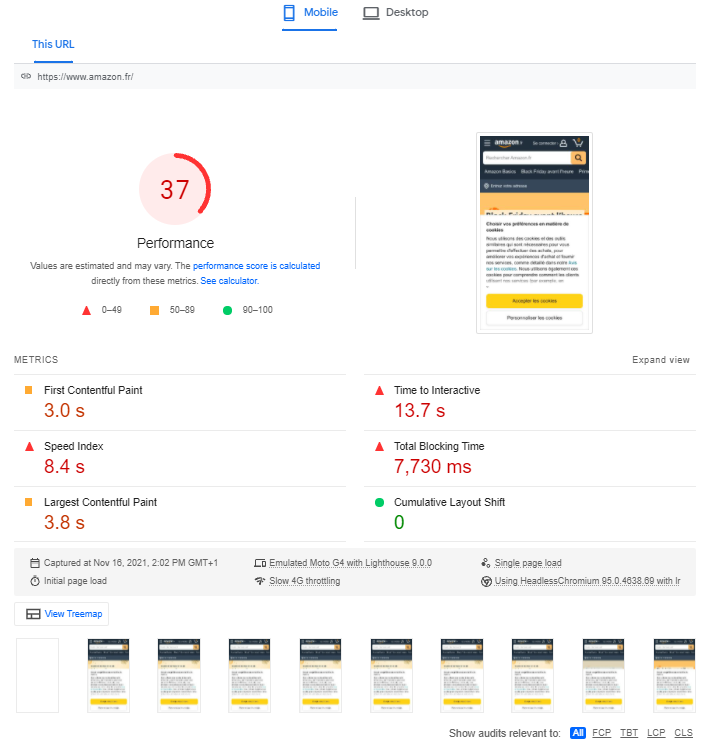

By simply entering a URL into PageSpeed Insights, Google calculates a performance score between 0 and 100 :

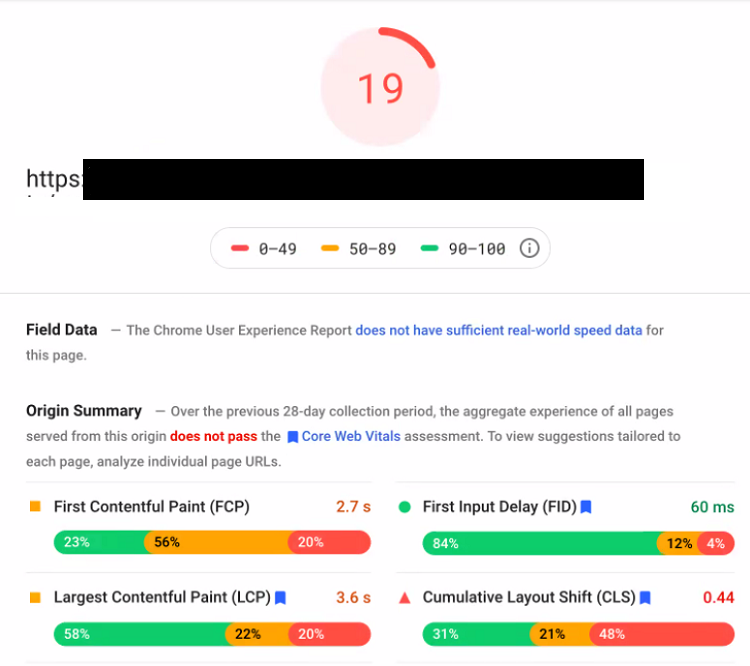

Google PageSpeed Insights resultspage

As a reminder, the search engine considers :

- 0 to 49: a web page is slow,

- from 50 to 89: a web page is moderately fast,

- 90 to 100: a web page is fast.

But how is this score established by Google? Is it possible to reach the holy grail: a score of 100?

To propose this score, Google relies on one of its other tools: Lighthouse. It’s important to remember that the data is collected by simulating browsing under conditions that are far from optimal, and that don’t necessarily represent those of your real users. More precisely, in PageSpeed Insights, the Lighthouse score is calculated by default as if your pages were displayed on a mid-range cell phone in “Slow 4G”.

These conditions are representative of an average for the entire global population, across all geographical zones, including those with the lowest network quality.

However, your audience is certainly much more local, or at any rate concentrated in a few countries where the bulk of your users benefit from network quality superior to Slow 4G.

Ideally, for a score closer to your reality, PageSpeed Insights should detect the location according to the domain name (e.g. .fr) and propose a score calculation based on average browsing conditions in this geographical area instead of the whole world (indeed, few sites have an audience covering 100% of the globe).

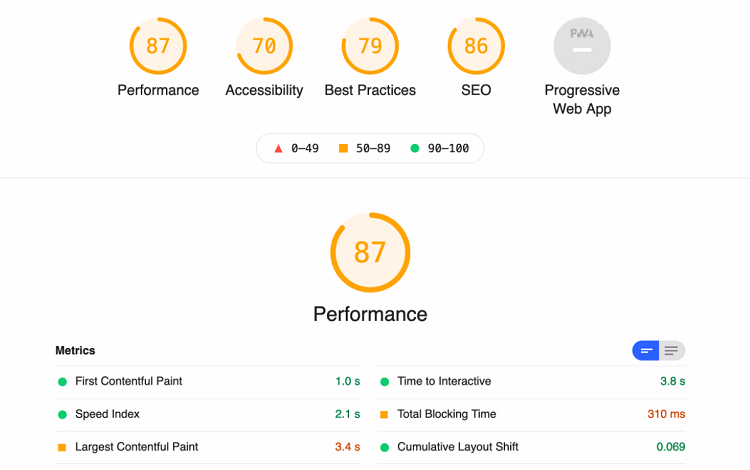

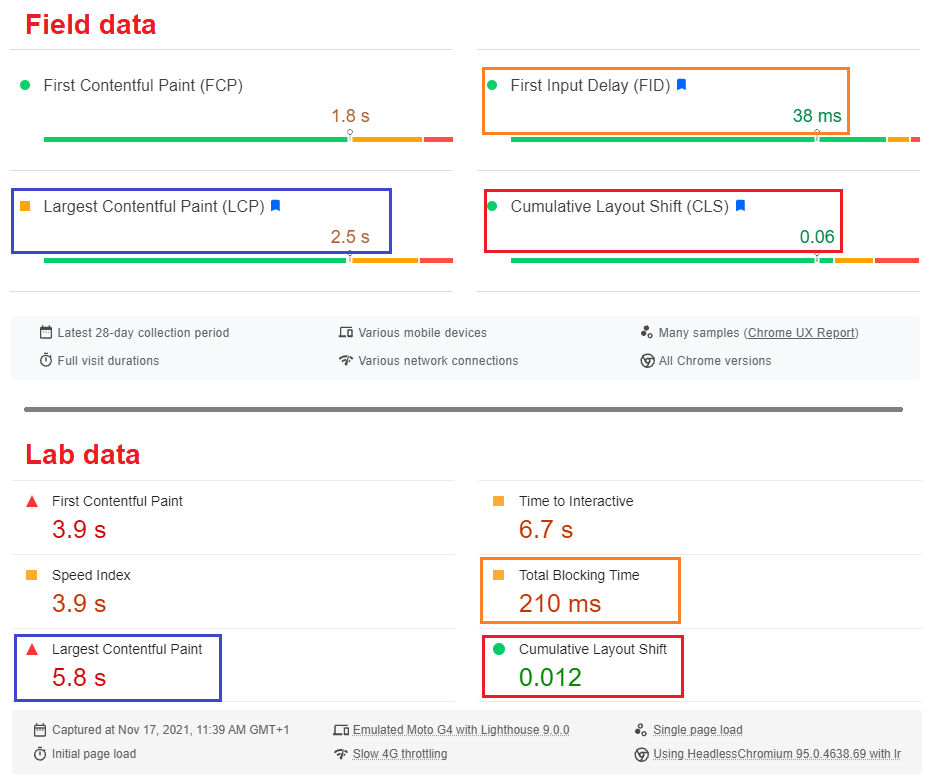

To help you better understand the impact of these browsing conditions on the Lighthouse score, we’ve carried out a test for the same web page (NB: these tests are carried out from the old Lighthouse and PageSpeed Insights interfaces, whose UI has evolved, notably to make it easier to distinguish between the different data offered by these tools) :

- with Lighthouse , simulating a 4G connection in France on a Motorola G4 model (the score is 87):

- and with PageSpeed Insights (under the conditions explained above, with a score of just 19):

The difference between the results of these two tests is significant, and this example illustrates the impact of the choice of navigation conditions on these performance scores (or rather the impossibility of choosing).

The first thing to remember is that the score indicated by Google is a snapshot at a given moment in time, based on browsing conditions defined by Google, which are not the most advantageous for translating the real speed of your web pages, and which are not necessarily representative of your users’ browsing conditions.

So how do you get Google to deign to consider your web pages as fast?

Let’s go behind the scenes of Google’s PageSpeed score calculation to understand what you can take into account to optimize the speed of your pages, and also how to take a step back.

Behind the scenes of PageSpeed Insights

On its results page, PageSpeed Insights displays the Lighthouse score, established under the conditions described above. To go a step further, you should know that it is calculated on the basis of 6 performance indicators, each with a different weighting in the score calculation (this article will help you understand how each metric is weighted in the calculation):

- First Contentful Paint, which evaluates the moment when the browser renders the very first element in the browser ;

- Speed Index, which evaluates the loading speed of elements above the waterline;

- Largest Contentful Paint, which evaluates the time it takes for the largest visual element to appear in the browser;

- Total Blocking Time, which adds up the blocking times of an interface before it becomes permanently interactive;

- Cumulative Layout Shift, which evaluates the visual stability of the page;

- Time To Interactive, which evaluates the time required for a web page to become permanently interactive without latency.

Thus, on the same results page, different webperf metrics that measure different aspects of speed coexist, divided according to how they are retrieved:

- Field data, gathered from the experience of real Chrome users;

- Lab data, collected on the basis of simulated navigations (as seen above, used to calculate the Lighthouse score).

Field data and Lab data are not retrieved in the same way,

which is why the same indicators do not display the same results depending on the method of collection.

In the test above (this is the new interface deployed by Google in November 2021), Field data shows that, according to Google’s CrUX panel data, 75% of users have an LCP of less than 1.8 seconds; but the LCP measured in Lab (Lighthouse) data is 5.8 seconds. This is yet another illustration of the fact that Lighthouse data (and therefore PageSpeed Insights) doesn’t always correspond to your reality.

To reinforce this point, let’s also note the difference between First Input Delay (real data, or Field) and Total Blocking Time (equivalent to FID in Lab data, to which we’ll return later).

We’ve seen that the Lighthouse score is based on TBT, not FID, and that TBT accounts for 25% of the PageSpeed score. So if your TBT is poor, the impact on your PageSpeed score will be significant.

However, you should know that FID better represents interactivity and the real experience of your users. Why?

Because FID indicates when the browser is able to respond to a user interaction; whereas TBT is an accumulation of periods during which your interface doesn’t respond to interactions. But these periods can accumulate at the beginning or end of the loading of your web pages without interfering with use!

Let’s take a practical look at the impact of taking TBT rather than FID into account on your PageSpeed performance score.

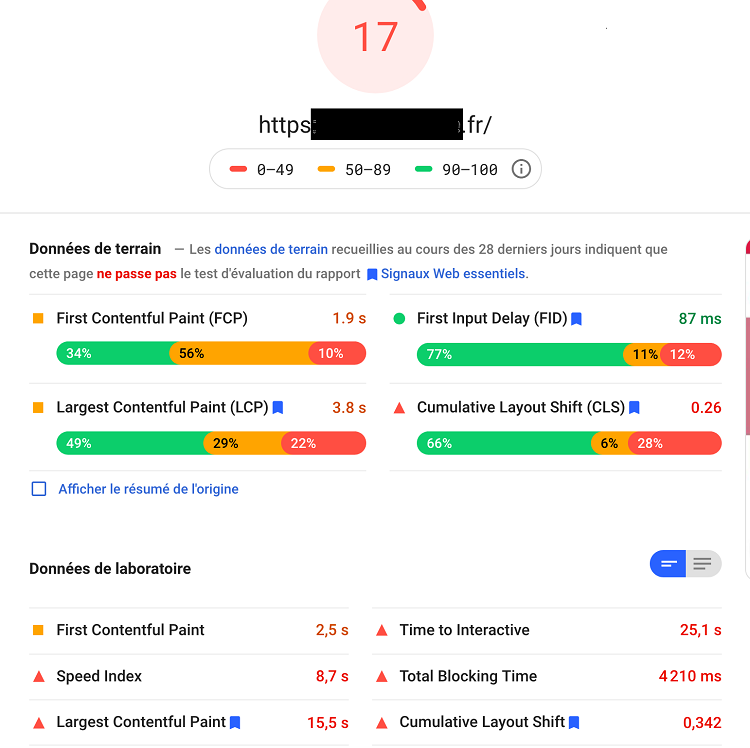

We’ve tested a page with PageSpeed Insights, and it scores 17. The FID is 87 ms, and the TBT is 4210 ms:

Then we took the field data (Lab) and integrated it into the Lighthouse Scoring Calculator (which shows a score without Slow 4G, therefore) to observe the score obtained.

For this test on the Lighthouse Scoring Calculator, we used the FID data (87 ms) instead of the TBT (4210 ms). And we can see that if PageSpeed Insights used FID instead of TBT, the score for this page would be 59 instead of 17!

This is yet another example of how Google rates your site under particularly severe conditions, and how – once again – the score obtained does not necessarily reflect the reality of the majority of your users, whose network quality is probably much better than that simulated by Lighthouse for PageSpeed Insights.

However, beyond the race for the PageSpeed score, everything you can do to optimize each indicator on your site will remain beneficial to the user experience.

What’s more, improving your Core Web Vitals is also good for your SEO, and it just so happens that Core Web Vitals are included in the calculation of the PageSpeed score:

- Largest Contentful Paint,

- Cumulative Layout Shift,

- and the equivalent of First Input Delay, Total Blocking Time (if you improve your TBT, which is Lab data , you also improve your FID, which is Field data ).

The PageSpeed score is thus made up of different speed indicators, each reflecting a different aspect of the user experience.

Some are “easy” to optimize, while others require considerable expertise. If you’re already working on your loading times, you may even have noticed that an optimization can improve one indicator while simultaneously degrading another. To avoid this problem, our engineautomatically applies speed optimization techniques while allowing them to be intelligently articulated in relation to each other.

So, now that you know the recipe for the PageSpeed Insights score, let’s see if all is well in the recommendations that Google offers on its results page.

Expert opinion with Anthony Barré, Software Engineer @ Fasterize

Note that the Lighthouse score takes greater account of the impact of JavaScript resources, with the increased weight of TBT and TTI since v6. As a result, complex sites such as e-commerce sites have seen their score drop without any change to the site.

Indeed, Google’s rating may have been good when interactivity was not taken into account in Lighthouse’s calculation. But now that the weight of TBT and TTI has increased, even if display speed is good, if page interactivity isn’t up to scratch, the PageSpeed score will be poor. In fact, since the Lighthouse update, this score has become much more interesting, and is even one of the most advanced among webperf scores.

That said, it’s important to remember that the Lighthouse score is calibrated against the millions of more or less complex sites that make up Google’s CrUX panel. This may give the impression of a poor score, but you have to bear in mind that a website is compared with other sites of no complexity whatsoever (blogs, pages without rich content…).

However, an e-commerce platform uses third-party services to enrich the user experience (A/B testing, chat, customer reviews, geolocation, etc.). This type of site therefore leaves with a structural penalty that Google does not take into account in its analysis and recommendations (a “rich” site can still achieve a good PageSpeed score in absolute terms, but this requires in-depth expertise and consistent, ongoing efforts that are best automated).

That’s why it’s more relevant to compare your score with those of your competitors, or with those of websites of the same level of complexity as your own, and above all, to observe the evolution of your PageSpeed score over time.

For example, looking at the top 10 of JDN’s summer 2020 mobile webperf ranking for the e-commerce category, it’s interesting to note that more than half of these websites have a score below 49 – thus considered slow by Google. Not a single one exceeds 90! This puts things into perspective, and allows us to situate ourselves in relation to our ecosystem.

Finally, it’s important to bear in mind that web page speed and performance cannot be summed up in a single score, and that different metrics need to be observed to really understand the stumbling blocks and the levers for improving performance.

Google audit recommendations: what to do to improve your PageSpeed Insights score (or not)

As you can see, you shouldn’t rely on a simple score to assess your site’s speed and performance.

And what about Google’s tips for speeding up your web pages? They too need to be taken with a bit of hindsight.

Some recommendations are basics for improving loading times, and SaaS solutions, CDNs or plugins can do this automatically – and even better than if you were to launch developments yourself. Others, on the other hand, require action on your part because they are difficult to automate.

Here are just a few examples of Google recommendations that should be applied with care:

Serve images in new-generation formats

This is an interesting recommendation, but depending on the number of images to be processed on your site and the way it is developed ( desktop/mobile version , responsive, adaptive), implementation can be tedious. Also, the same compressed image does not require the same decompression time depending on the browsing context, and particularly on the power of the device. An image compression plugin or tool can help; and better still, a front-endoptimization solution such as Fasterize, to intelligently compress large volumes of images at lower cost and serve up the right image size according to screen and browsing context.

You should also be aware that the gains estimated by Google in its audit are often well above reality. This is in fact a recommendation aimed at pushing the WebP format that the search engine has been promoting for some ten years, but without the expected success since compatibility with all browsers is recent. The AVIF format offers better performance, and our engine enables you to access this compression format very easily to offer your users the best experience with optimum loading speed.

Reduce the impact of third-party code

This is another very good suggestion. In concrete terms, your site certainly needs to call on third-party scripts for certain functionalities (chat, search, content personalization, A/B testing, analytics…), and perhaps even your business model depends on them (advertising). But as their name suggests, these third parties come from outside, so you have no control over them. The best thing to do is to prioritize yourscripts and defer loading and execution of those that are not critical to the page’s operation.Lightweight pages (optimized CSS, HTML and JS files) and optimized scripts allow you to absorb the extra weight of those Third Parties that add value to your site. Rigorous management of third parties and an audit of the usefulness of scripts inserted on your web pages should be carried out by in-house technical teams, as these tasks are much more difficult to automate.

Preload key requests

You obviously can’t pre-load all resources with <link rel=preload>, as this would create the very traffic jam you want to avoid. A browser already defines the priority of each resource , and modifying these priorities can create the opposite effect of what you want.

On the other hand, you can apply preloading to any resource that is critical to the page and not easily discoverable by the browser. Depending on the resources in the critical path, you may also apply this preloading to fonts if no font-display strategy is applied. It’s important to prioritize these resources (an advice that applies to all webperf best practices).

In conclusion, you can consider your PageSpeed score as one signal among others, but not as a definitive mark of the speed of your web pages per se. In fact, Google is constantly researching this score, as new metrics are discovered.

It remains an interesting and easy-to-access tool for evaluating your site’s performance, to identify the broad outlines of what you need to optimize at any given moment. On the other hand, to monitor your performance over time, it’s best to equip yourself with dedicated webperf tracking tools.

In short, if you have a “bad PageSpeed Insights score“, it doesn’t necessarily mean that your site is slow for absolutely all users in all contexts. It’s a sign that you need to work on your loading speed, and to do that, you need to choose wisely which metrics and techniques to focus on.

To find out more about the main webperf. metrics, and how to measure and improve them, click here,

how to measure and improve them: